I’ve been thinking about the future of conservation. To chart a path forward, it helps to know from where we came. While researching, I keep returning to the writing of Robert Francis. On his blog, Bird History, and in a forthcoming book Republic of Feathers: A Bird’s Eye View of America, Robert recounts conservation history, and American history more broadly, through delightful stories of our ever-evolving relationship with birds.

In this conversation, Robert shares the origins of bird names before we move into why birds offer such a rich lens on American history and what our changing relationship with them can tell us about conservation and progress.

Transcript:

Editor’s note: The transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Origins of Bird Names

Grant Mulligan: Let’s jump right in. One of my favorite bits of yours is that you are a bird name enthusiast. On X and in many of your posts, you talk about where bird names come from. I’ve got Monet’s painting “The Magpie” behind me. How did magpies get their name?

Robert Francis: In the 1400s, the English had this endearing practice of giving birds people names. You had Tom tit, Jenny wren. There’s also a bird called a pie, and they called it Margaret pie, or Maggie pie, and that just became magpie. There are other birds that this happened to as well. There was a bird called a daw, and they named him Jack, so that became Jackdaw.

There’s a bird called a redbreast that they named Robin. Robin redbreast became so popular and attached that the original redbreast fell away. That name has spread all over the world too. American robins are named after English robins, which were just a nickname. It was like we had all these birds flying around and we’d call them Steve, and that just became the name that we call them. This is something that has a six hundred year history. It shows that people, the culture, and history have these long through lines for the birds we see around us all the time.

Mulligan: I had no idea that it went back to the 1400s; that is a long time. Obviously people would’ve had names for the birds around them, but the fact that they were just common names, that weren’t particularly descriptive, and yet those names have stuck through time cracks me up.

Birds and American History

Mulligan: You already jumped right into where I was hoping to go, history and birds, and how these two things are tied together. What is it about birds in particular that make them relevant to recounting history, particularly American history?

Francis: Nowadays, we often think about birds as window dressing, something that’s fun and interesting to talk about and think about. There are people who like watching birds, but we feel like they exist out there. They lead just completely separate lives from ours.

If you go back through history, birds were woven much more deeply into people’s daily lives. We used birds to stuff our mattresses with bird feathers. [Wild] birds used to be a regular part of people’s diets. What’s most interesting to me is seeing how all of the conflicts and contradictions that are core to American history and identity can be seen playing out in our relationships with birds. Conflicts over race, over gender, over class, and conflicts between the north and the south all show up in the ways that people have treated birds over time.

There are reasons that birds are special; that they’re different than other classes of animals. When we push the wilderness back, when we live in cities, other than rats and squirrels you don’t see a lot of mammals. But birds, we can’t keep them out. I live in New York City, and it’s one of the best places for seeing birds in the country. Central Park is flooded with migrating birds every fall and winter. New York skyscrapers are famous for being homes for peregrine falcons and kestrels that nest and hunt pigeons and rats. Birds follow us around. It’s a very normal thing to see a really wide range of birds in the city.

We don’t have this same city/nature dichotomy in the same way that you might expect with other classes of animals. You can’t keep them out. Over the country’s history we have tried to push back the wild and kill off the animals we see as vermin, like bears, wolves, and coyotes. Birds are still with us, and they stayed with us, and if you keep your eyes open, you know you’ll see them. We don’t live separated from nature as much as we pretend, and birds are maybe the best demonstration of that.

Mulligan: I think you’re right. One of the reasons birding has been such a hobby of mine for many years is that everywhere I’ve traveled there are birds. I grew up in Arizona and they’re part of the backyard fabric. I still feel like I’m home when I hear certain calls, like a cactus wren or Gila woodpecker, birds that have these narrow ranges that are close to my home. Then I’ve traveled to Wisconsin and there are different birds there. South America, Europe, you see birds everywhere. You can see them in Paris. You can see them in the jungles of Costa Rica. There’s something about birds in particular. I hadn’t quite thought about what makes birds so different compared to mammals, that they can still be such a core part of our storytelling.

How did you get interested in the intersection of birds in history? I know people who like history books. I know people who like birding. I’ve never seen people meld them together in quite the way that you do. What brought these two passions together?

Francis: Several years ago I was in a book club reading The Power Broker by Robert Caro, and I was marveling about this guy who dedicated so much of his life to writing about one person. Caro spent 10 years writing this book about this, until then, obscure bureaucrat in New York that had a fascinating life and a huge impact on the city. Somebody worth writing a 1,200 page book. Then he spent the next four decades writing about Lyndon B. Johnson. I was having a conversation with a friend in this book club about, if you were in Caro’s position, what would you spend your life writing about? My friend asked me this, and I said something like birds and US history. She said “you should write that book.”

That got the wheels turning in my head. I was familiar with birding history and ornithology. There’s a lot of writing about famous and influential ornithologists, but there isn’t so much about how ordinary people interacted with birds. I think now we associate birders with people who have this hyper fixation, who like to learn all the bird names and go just look at birds. Today that’s what interacting with birds looks like. But over the last 400 or more years of America’s history, that’s a pretty recent development.

People still relied on birds for their income. They saw birds as pests. They used birds to decorate their hats. There were a lot of different ways of interacting with birds, and the more I looked into it, the more that I saw how deeply it went into so many people’s lives. In ways that are surprising. Not just their lives and their incomes, but the conflicts that we have as a society.

This fits within the broader field of environmental history, of understanding our relationship with nature. Taking a longer view, there are many different kinds of people that lived in the United States, and all of those people, all those classes of people, had different relationships with nature and different relationships with birds.

Mulligan: I remember going to Wisconsin where I first fell in love with birds. I’d live with my grandparents during the summers, and my grandpa loved robins because he said they were proud birds. They always had their heads held up high and their chests out. And I think he would see a robin and stand up a little straighter.

He and my grandma also loved house sparrows. I asked them, “why do you like house sparrows so much?” It’s because the sparrows never left. All the other birds leave, and in the winter, when they’re lonely, those still come to the feeder. Sparrows were friends who stayed with them and had deep meaning for how they went about their lives. Those aren’t stories that get told often, but as you’ve gone through this history, those stories are very real, and they do give us a sense of the fabric of the day to day life of average Americans.

Francis: Yeah, exactly. I’ve been reading recently about this idea of honorary pets, birds that are wild, but that we see as somehow connected to us. One writer talked about bringing them into our moral community, like these robins. You wouldn’t kill a robin, right? You wouldn’t kill a bluebird. You’d go hunting for a mallard, you’d go hunting for a Canada Goose. They’re food. But these other birds, like Eastern bluebirds, they’re special, and we protect them. We like them. We feel involved in the daily dramas of their lives.

New York City also loves its celebrity birds like Flako, the Eurasian eagle owl that escaped the Central Park Zoo and lived in the wild for a year before that. There’s Barry, the barred owl that lived in Central Park. There was “Hot Duck”, a mandarin duck that lived in Central Park too. These are pieces of people’s lives that they get invested in. People are drawn to that sort of connection. Even if they don’t think of themselves as birders, birds still have a way of intruding into our lives and making us feel that connection.

From Exploitation to Protection

Mulligan: You write a lot about these relationships and how they’ve changed over time, including economics of ornithology and how we used to think of birds as pests instead of something valuable. There was a cultural change that happened there. Let’s do a brief history of how we went from direct use of birds and exploitation to measuring their value, and then more aesthetic/cultural values. What was it like and how did we use birds when more direct engagement and consumption was part of everyday life?

Francis: Yes, right. That’s how I think about this broad arc of history of our relationship with birds. The movement from exploitation to protection over the last several hundred years, and the revolution that it took for taking our relationship with birds from one where they exist to be consumed to one where we see birds as deserving protection in their own right.

This change took place over a pretty short period of time, around the turn of the century. It wasn’t just a change in people’s values, although it was that, it was really a revolution. A legal revolution, a cultural revolution, an economic revolution, and a social revolution in how we relate to nature. There are many forces behind that. There were sportsmen, wealthy gentleman hunters, who saw people who were hunting birds by the thousands, by the tons, to bring to urban markets. They were killing all the birds that the sportsmen themselves thought that they were owed or had a right to, so they sought to change laws to make it so that the only people who could hunt were people who hunted like them.

The sportsmen helped lead the transformation of wildlife laws that we still have in the United States today. Which is you can’t sell birds. There’s no market for birds. It goes against federal law. You can hunt them for your own use. You can give them away, but you can’t sell them. So they achieved this change to destroy and eliminate the market for birds, which used to exist at an enormous scale. The markets had led to the extinction of passenger pigeons and the near extinction of a lot of other species of game birds. That was one axis that this change took place on.

Another one was the feather trade which is related. In the late 1800s it became really fashionable for women to wear hats that had feathers on them, which led to the mass hunting of herons, egrets, gulls, terns, and really anything that had attractive feathers. That gave rise to bird protection movements that were again largely driven by wealthy northerners, often women, who tried to end this practice and campaigned to end it. That led to the founding of the Audubon Society and other conservation groups.

Another axis here was, as you reference, economic ornithology. Before the 1930s and 1940s there were ineffective insecticides that farmers could use to protect their crops. There was this common belief that the only thing standing between the crops and these insect hordes were birds that would eat insects and insect eggs. There’s an entire government division that was created in the 1880s to study the impact of birds on agriculture. It became widely accepted that insectivorous birds, as they called them, were responsible for and sometimes solely responsible for protecting crops from complete destruction by insects.

Finally, there was this cultural change where certain birds came to be seen as innocent and worthy of protection. There were a lot of Audubon and other conservation leading organizations that worked in schools to change perceptions and teach children that birds should be protected. And teaching the public that birds should be protected as well. In the Progressive Era, you had these moralizing improvement movements that sought to improve working conditions and were part of a broader movement for societal improvement. Birds were one facet of that to create widespread protection.

All this culminated in 1918 with the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. It completely banned the market for birds, banned killing a long list of birds, except for a few that people were still able to hunt, the game birds that we think of today. This is more than 100 years ago, and it’s still the foundation of bird protection that we have today.

The last thing I’ll say about this is we went from this place where you could go to the store and buy robins, you could buy a whooping crane, you could buy passenger pigeons, all for your dinner. You could buy hats with feathers from great egrets on them. They were hunted in Florida. You could go out and catch a mockingbird, keep it in a cage, and keep it as a pet. We’ve gone from that to where all these birds are protected. Birds are doing better than they were for the most part, 130 years ago. But I think we’ve also lost a bit of intimacy with nature. We don’t need to use them. We might appreciate them from a distance, and a lot of people do, especially with bird feeding. But I think we also have lost touch with the birds that we’re still surrounded by.

Changes in cultural values

Mulligan: That’s a great summary of several decades worth of bird conservation history. I’m curious what you think motivated some of these changes? I’m interested in the idea of progress, and one of the things that jumped out to me was the change in robins in particular. You have a great essay about robins on the dining table. It seems to me that there’s some element of agricultural progress that changed things. Farmers were killing birds competing for the crops, and then a government agency said no, we have more science, we can actually show that the birds are beneficial, not harmful.

At the same time, as you get more food and cheaper food, it’s much easier to go to McDonald’s and get a burger than it is to go hunt a robin, cook it up, and put it on toast. I’m curious from the perspective of robins as a case study, because you’ve written so eloquently about them in multiple essays, how that change in culture might be a function of progress among other dimensions.

Francis: That’s an interesting question. There were a number of ways that people would consume robins and consume other birds as well. Some was subsistence hunting, so people needed food and hunted whatever they’re proximate to. On the other side is consuming birds as a luxury good. Often you had those two acting in opposition to each other. There were the affluent northerners who often had this idea that it was poor southerners, and particularly blacks, they called them pot hunters, that were responsible for killing a lot of birds that they thought should be protected.

Mulligan: Tell me about how robins were consumed because I thought that was a really interesting story. Robins on toast and robin pie. So who was eating them? Why and where? Where did the change happen specifically around the time that the cultural norms were changing for migratory birds. Was it aligned with this idea that we’re over exploiting birds, whether for food or for hats, or were they on their own trajectory?

Francis: This is all wrapped up together. Robins were a very interesting species because they’re migratory. They spend their summers in the northern part of the country, and they gather in huge flocks in the South. If you live in Massachusetts, you might see robins during the summer in small groups, a small handful of them here and there. They’re a beloved companion during the spring and summer months.

If you live in the south, you see them by the hundreds of thousands, sometimes tens of thousands. At least this was the case 100 or so years ago. They weren’t eating your crops. They were just hanging out in these massive flocks and people there saw them as this explosion of natural abundance. They were a resource that was waiting to be taken.

In the North, you had these preconceptions and evolution in understanding that occurred during this time. As birds migrated, the same birds that people were hunting in the South were the same ones that were visiting you in the North. They were killing your robins, and you saw robins as protectors of your crops. If they’re killing them in the south, that means these southern pot hunters, who you already are prejudiced against because they’re poor, they’re black, and they’re using unsportsmanlike methods to shoot robins, are directly harming your crops. So you see these campaigns. Some are more benevolent. They’re trying to educate people about robins. Some are more aggressive and racist, really, to try to change laws, impose laws from the outside, and to get people to protect birds that you see as your own.

Again, the ways that the people in different parts of the country and on different economic lines are consuming robins are different in upper class restaurants where you might have them serving robins on toast. What I saw references to from these newspaper articles that were 150 years old, is that lower income people often eat robin pot pie or something like that. So I started writing this essay thinking that I’m going to find some interesting ways that people used to eat robins. But really, what I discovered is that there are much deeper class and economic conflicts that resulted in campaigns to protect robins.

Mulligan: I find the robin stories fascinating because it’s not only a great way to look at the history of how birds got protected, but it tells us so much about how environmental values change over time and the way that they are imposed. Part of me thinks what a great achievement the Migratory Bird Treaty Act is. We don’t kill all these birds. We understand the science of how they migrate, how important it is that we protect them across their entire path, particularly where they breed.

It’s also hard not to think at times that it’s an example of environmental protection going too far. Is there a reason why you couldn’t have a catch limit on robins in the same way that where I’m from in Arizona we’d go hunt mourning doves and quail? We could do it in a sustainable way, in a particular season. It strikes me as the classic all or nothing environmental protection approach that we’ve had for a long time. I’m curious how you think the robin and some of these stories relate to modern challenges that we face in conservation and getting good environmental laws on or off the books appropriately.

Francis: It’s interesting thinking about what birds we consider eligible to be food and which ones we don’t. I think the reason that a mallard is food, or a chicken, for that matter, is food, but a robin is not, is a reflection of class and history and values. Could you sustainably hunt robins? Of course.

Do I think that that means we’ve gone too far with protection? One of the developments of this conservation movement, really this revolution in our relationship with nature, is going from this idea that anything in nature is yours to consume. America was a boundless country, and anything you could capture and eat and hunt was yours to consume. What this revolutionary legal change did was say that actually birds are wards of the state. They belong to the government, and it’s the government’s prerogative to determine what and how much you can take. Because these are our collective nature, our collective heritage, I guess you could say.

It’s a reflection of our collective values. What we decide can be hunted and what shouldn’t is imperfect, but I also don’t know a better way to make those considerations within the bounds of what protection actually looks like or what the limits should be in order to protect birds to the degree that they need to be.

I will say on the other side of this is that we had this understanding that birds were important and necessary for agriculture, and then we stopped needing them. We discovered in the 40s effective insecticides, effective pesticides, effective ways of protecting crops from insects. People stopped needing birds to protect their crops, and then this created ecological dead zones as a result of mono-cropping. As harmful as hunting was for many species of birds, the transformation of the country into farmland, the destruction of wild and the great American prairie, the over application of pesticides and insecticides, and the decimation of insect life in the country has been just as harmful. We think of hunting as being harmful to animals, but there are other ways that we interact with the natural world that are much more damaging. There isn’t much legislation to prevent those harms from being done or I should say that they’re not aggressive enough to prevent the widespread loss of biodiversity that we’re seeing today.

Mulligan: That’s a super interesting point, because it gets to some of the interesting arcs of conservation and environmentalism over time. Aldo Leopold and A Sand County Almanac, or some of these others that come before the Migratory Bird Treaty Act is passed, they’re very much focused on direct exploitation. We are over hunting. There were bison, there were egrets, there were herons. Passenger pigeons are a great example; we’re just wiping them out because we’re being completely unthoughtful about how many we can take.

But environmentalism shifts later on to - we don’t need these species anymore. We don’t rely on them for clothing nearly as directly. Don’t rely on them for food nearly as directly. We don’t rely on them as an ecosystem service for keeping down pests. You lose those values, and so in return, you get the intrinsic values that really rise to the forefront of how we talk about these things.

But we’re also talking about indirect taking. The things that we’re doing like habitat loss or other things, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring book being the best example. We’re spraying DDT to solve one problem, but this leads to thin shells that nearly wipe out the bald eagle, the symbol of America. Through birds, you get not only the history of America, but how conservation and environmentalism has really evolved over time and for different reasons.

One of the things that I’d be curious to get your take on is what it might look like going forward. There’s probably still indirect things that we need to solve for. Then I’d be interested in your take on what active restoration might look like, and if there’s something in bringing birds back and not just keeping the harm from being done. Is there something on the horizon you’re excited about, about the act of restoration? What are the indirect things that are still going on that we might have overlooked and/or most people may not know about? And then we’ll get into where you see restoration and conservation for birds going from here.

Modern Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation

Francis: It’s really complicated. One of the big challenges with conservation today, or the way that the challenges facing birds have changed over the last 100 years, is in this era of market hunting around the turn of the century, what really needed to happen is people needed to stop killing birds. Birds were being killed by the millions, by the tons, and a lot of the changes that needed to happen were just to stop doing that. Once that happened, a lot of species could recover.

There were also issues with ecological destruction and habitat destruction that were happening at the same time. The United States did a lot of wetland restoration especially to restore habitats for migratory waterfowl which happened to be the birds that hunters were seeking. One of the most significant conservation successes was restoring the populations of most widely hunted birds, not just through protection and regulation, but also through creating the ecosystems they needed in order to thrive.

Going forward one of the big challenges is that there isn’t just one change that everyone needs to get behind. Something similar to just stop killing the birds. There are a multitude of threats. Each species faces its own array of threats and risks that need their own distinct understanding of what’s challenging, of what’s harming, and what’s killing off a particular species and what needs to change in order to protect that species. There are broader threats, above all climate change and habitat destruction, but I remember reading about one of the biggest mortality factors for prairie chickens is flying into barbed wire. It took a long time for people to understand that this was actually a pretty significant cause of their mortality. The remedy for this is putting tape or tags on barbed wire so that they see the fence and don’t run into it. This is something that affects a small number of species but affects them pretty severely, and it’s a specific change that needs to happen.

You multiply this for dozens and dozens of species that have lost more than half of their population in the last 50 years. Again, there are things that will help a large number of species like the lights out movement to protect birds from crashing into windows which kills a billion birds every year; that’s a big one. But there are a lot of distinct challenges that each bird faces.

You asked what I’d like to see. I’m not an expert in conservation or ecology. History is where I spent most of my time. But one thing that I have seen is that, again, at the at the turn of the century, when this conservation movement was really growing in power and was able to achieve these really incredible gains in conservation, it was a political movement that drew across hunters and conservationists and farmers and children all on the same page about changes that needed to happen. Today, you have tens of millions of people who are birders. You have 50 million people who have bird feeders outside their homes. I see this as a natural constituency. People who are interested in birds, interested in their welfare. Birders spend something like $100 billion every year on things related to birds and birding. Travel, equipment, whatever.

But birders don’t behave like a constituency. There are a lot of different changes that need to happen in our relationship with nature to protect birds and stop their sometimes precipitous population decline. But I don’t think the solution is a scattershot approach. I think it is to create a movement that puts pressure on politicians to regulate and fund in such a way that birds receive the protection that they need, whatever that might look like.

Mulligan: I do think the constituency and the economic numbers are interesting. People really care about birds. To your point, when I was a wildlife biologist, I’d stay in these little motels outside of wildlife refuges and other places where I was doing surveys. You would be surprised at the percentage of people in these small towns that are there just to bird and how big an economic driver it is for many places whether they’re bird Meccas or an opportunity to see a particular species. How do you organize those people together to get outcomes or funding who would want to make some changes? I think that’s a super interesting question.

Extinction, restoration, and favorite birds

Mulligan: Switching gears away from the history of birds and conservation progress, you’ve written a lot about bird extinction. If I gave you the chance to see a single specimen of one of these extinct birds, which one would it be? And, if different, what would you love to see thriving as a restored species if we could rewild and bring back a species to its historic range? What would you be most excited to see of what we’ve lost?

Francis: I spent a lot of time thinking about passenger pigeons. I think that they’re interesting and beautiful, but I don’t know that they’re that outstanding. They look like a mourning dove, just bigger. The reason that they’re so notable, or were so notable, is for their numbers. I love asking people to guess how large they thought passenger pigeon flocks could get, how many birds might be in them? People will say 1000 or maybe 10,000 in flocks. But estimates are that they could get up to 2 billion birds, which is a number that you can’t even comprehend.

There are these stories of people watching flocks of passenger pigeons fly over in a stream a mile wide, going at 60 miles per hour, and passing overhead for 14 hours from sunrise to sunset. We hear stories about the massive herds of bison thundering across the plains being like that, an indispensable American scene. I think these massive flocks of passenger pigeons were similar. Sometimes they’d fly over Chicago or St Louis, and people would stand on their roofs and shoot into the flood pouring over their heads.

It makes me really sad that I’ll never get to see that. I have seen the last passenger pigeon. Her name was Martha. She’s owned by the Smithsonian Museum, so they had her own display a while back. So I got to see her. It did feel like an emotional experience being close to something that used to be such a force of nature, but through over-hunting and exploitation of the environment they disappeared.

There are a lot of people who get excited about deextinction, and I will say that’s something that I’m pretty skeptical of. I think if they ever manage to claim to bring back a passenger pigeon, it won’t be the same thing. I think that they really are gone, which is deeply tragic, but it’s also a reminder of the fate that could fall on any species of bird or any species of living thing. We have a deep duty to protect them, because nothing’s inevitable. The extinction of the passenger pigeon wasn’t inevitable, and the preservation of robins is not inevitable either.

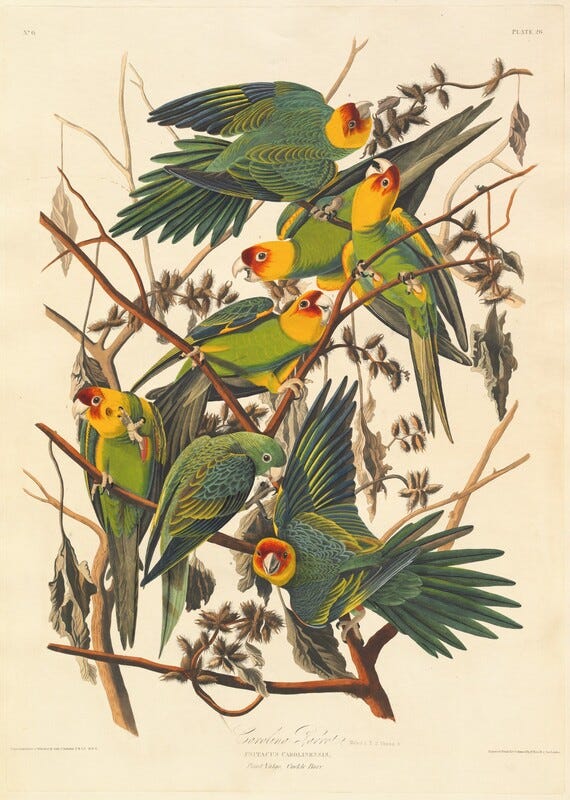

Mulligan: Mine, if I could see one, is a Haast’s eagle from New Zealand. They were big enough to hunt moas. I don’t know if I want to see a lot of them back. Sounds a little frightening to go for a hike with my kids someplace where there’s eagles big enough to haul off moas. The passenger pigeon, that feeling of what it must have been like to watch a flock fly over, I could’ve done that forever. You and I have actually spent time seeing bison together out in Rocky Mountain Arsenal Wildlife Refuge. Wouldn’t it be great if if we could go back and see some passenger pigeons? Now a couple shorter questions. What makes the Carolina parakeet so interesting?

Francis: So there used to be a species of parrot in North America called the Carolina parakeet. It was the only species of parrot native to North America. Their range stretched from New York to Iowa down to Florida. It was adapted for cold weather. We have accounts of sellers and explorers seeing flocks of parakeets in the winter. They’re beautiful and charismatic, and they also went extinct. The last confirmed parakeet died in a zoo in 1918. I don’t know that the species itself is so exceptional; there are a lot of species of parrots, but it’s the one that was ours. It’s the one that we had here. I’ve kept John James Audubon’s painting of the Carolina parakeet as my phone background for the last several years both because it’s a beautiful painting and because it’s a reminder of what we’ve lost and what we still need to preserve.

Mulligan: I’ve got 12 Audubon prints behind me here on the wall. I don’t have the parakeet on it. I’ll have to also get it into the rotation. Favorite bird artist?

Francis: That’s a great question. There’s a lot of good ones to choose from. I think if you look at my apartment and see who’s best represented, it would be Charley Harper. He did a lot of abstract bird art. If you have the Merlin app on your phone or anything from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, he designed those logos years ago. I have some posters that he did for the National Park Service. It’s just fun, abstract ways of representing recognizable and beloved bird species.

Mulligan: Charley Harper images are some of my favorite puzzles to give at Christmas time. A lot of people get Charley Harper puzzles for me. Favorite state bird?

Francis: This one might be Utah’s, which is the California gull. It’s almost a joke. One state picked a state bird that’s named after another state. But there is actually a really good story here, which is when the Mormon pioneers first settled Utah, there was a plague of crickets that threatened to ravage their crops, and these gulls came in and feasted on these insects. The settlers attributed that to saving their crops that year. Since then they’ve had a revered place in Utah culture and society. I grew up Mormon and grew up sharing these stories about the miracle of the gulls, and it’s a deep connection. Many states picked their state birds in the 1920s or 1930s by having school children vote on which bird they wanted. Even though Utah’s bird is named after California, I think they have a much deeper connection to their state bird than maybe any other state.

Mulligan: I’m not surprised that your favorite has a detailed history to go with it. My favorite is the cactus wren. I can’t see one of those and have a bad day. They’re great. Such a cool sign of home for me. And I should go back to my favorite artist. I give a lot of Charley Harper puzzles, but Mincing Mockingbird is my favorite. If you haven’t checked it out, they do some great stuff. It’s a husband and wife team. They do detailed artwork, and then very silly, meme-y style birds that I give out as thank you cards all the time.

Before we get to our final question, thank you Robert for doing this and coming on with me. A reminder to everyone listening that you can find Robert’s Substack Bird History or find him on X where he posts, I wish I could call it a tweet, about bird belt buckles, bird names, and other great bird trivia. I always get a kick out of what Robert has to say there. My final question then is what’s your favorite place to spend time outdoors?

Francis: I mean, no place is a bad place to spend outdoors. I would say Cape May, New Jersey. For the last six or seven years, I’ve gone down for every fall migration. It’s at the bottom tip of New Jersey above the Delaware Bay, and it acts as a natural funnel for birds migrating south. They gather at this tip to wait for favorable weather to fly across the 14 mile wide Delaware Bay. You can see thousands and thousands and thousands of birds. I’ve had days where I’ve seen hundreds and hundreds of northern flickers, thousands of blue jays, thousands of swallows and thousands of warblers. It’s a really exciting, fun, fun place to be. Birders gather in almost as big as numbers. It’s a place with a lot of stories and a lot of connection.

Mulligan: Thank you for the time of day. It was great talking with you. Hope everyone reads your Substack, Bird History, and I look forward to Republic of Feathers coming out. Happy to be an early reviewer to get a peek; I don’t know if I can wait till the actual publication date. Good luck with your writing, and I can’t wait to read it.